This week we celebrate World Humanitarian Day, honouring aid workers around the world who dedicate themselves to helping people to recover from humanitarian crises every day. Here we hear first-hand from Ciara O’Malley who leads Oxfam’s humanitarian work in Juba in South Sudan:

It’s funny to think that I grew up not far from the Oxfam shop in Rathfarnham - now I’m working for them thousands of miles away in South Sudan.

I moved here from Pakistan, where I spent nearly three years working with Trócaire in communities affected by natural disasters such as floods.

You face a number of the same challenges in going to Pakistan or South Sudan as you would going to any other country, be it Australia or Canada, in terms of trying to find your feet. It’s a new job and team you’re working with, you’re also trying to make new friends, and you have to figure it all out, from working out the currency to where to do your food shop.

![]()

Above: Oxfam's Ciara O' Malley who is leading our humanitarian work in Juba in South Sudan Photo: Sorcha Nic Mhathúna / Oxfam

Of course, there are certain things you pick up along the way. ‘Load-shedding’ is a key word that comes up frequently in conversation in Pakistan, the term for the rolling power cuts that can last for up to 12 hours a day. That was certainly something to contend with when you’re without air-conditioning in 45 degree heat!

The first month or two I was there I was convinced that I was definitely not going to stay a day longer than the planned year! But I ended up loving it. I also met my boyfriend there. He is a British diplomat based in Pakistan, so that may have been a major contributing factor for why I stayed so long in Pakistan!

Now that I’m in South Sudan and he’s still in Pakistan, it’s the ultimate long-distance relationship but I find the key is decent internet connection so that you can Skype each other as well as having a defined end point of the long distance.

I was really interested in working in South Sudan for a number of years. Being a new country that is now just three years old, it has great potential but it has been wrecked by decades-long civil war, and now that conflict is being divided along ethnic lines. What’s unfolding here is a complex emergency where there’s ongoing conflict but also a severe food crisis. It’s a very challenging environment to work in.

South Sudan is a dusty place, but when you’re landing, you see that it’s surprisingly green (not unlike Ireland) because of all the sun and rain it gets during the wet season. I live in Juba, which is the capital but it is quite small. South Sudan is one of the most underdeveloped countries in the world. But despite having little or no proper roads, people in Juba are pretty good at following the rules of the road.

The South Sudanese are very friendly people but are initially quite reserved. Once you develop a relationship with them they’re extremely warm and caring people.

![]()

Above: Oxfam's Grace Cahill talks with Martha Nyandit (42). Martha and her six children are amongst the thousands of people who have fled several rounds of violent and bloody fighting in and around the town of Bor in Jonglei state. (You can read Martha's incredible story of survival story here) Photo: Pablo Tosco / Oxfam

Managing humanitarian programmes is a lot of responsibility. Trying to get your first break is the hardest part; it’s a mixture between luck but also a lot of hard work and you constantly have to be proving yourself. Aid work is a very competitive sector to break into with a lot of extremely well-qualified people looking for jobs.

I think the recession made it more difficult to get those jobs, as quite a few people who were made redundant from other sectors decided they wanted to transfer their skills and work for a non-profit. Moreover due to the cuts in the government overseas aid budget and the fall in public donations, many aid organizations had to reduce the size of their programmes and make a number of staff redundant.

I was one of those unusual people who always had a plan of what I wanted to do! I didn’t always know that it would be specifically humanitarian work but I always knew that it would be something in the international sector. When I was in secondary school at Notre Dame in Churchtown I was very involved with human rights campaigning and that really got me interested in this whole area of international development and humanitarianism. Then I went to study Politics and French in UCD as I thought that having a language would be an asset for this line of work and that politics would also be relevant.

After a volunteer role that turned into a paid position in development education at Suas, I went to University College London to do a master’s degree. I came back to Ireland to finish my thesis and started working in Trócaire in their humanitarian department as an administrator. Of course my passion was programming so when I got a job on their trainee scheme in Maynooth head office, I jumped at it. After doing that for almost a year, I was itching to spend time working overseas so when a position on their trainee scheme in Islamabad came up, I didn’t hesitate to apply!

In South Sudan, I live with 19 of my colleagues in a shared Oxfam house. I’m the only Irish person. My colleagues come from Portugal, Spain, the UK, the United States- it’s quite a mix. We each have our own bedroom and bathroom but we share a kitchen and living space so it can be quite crazy. Aid work is very full on. You work, live and socialize with your colleagues; it’s a very intensive and definitely not a ‘9 to 5’ job. Thankfully my colleagues are fantastic and we get along really well!

We would all usually work six if not seven days a week. I recently worked for 30 days straight without a break and a number of those were 14-hour days. I was completely exhausted by the end of it.

![]()

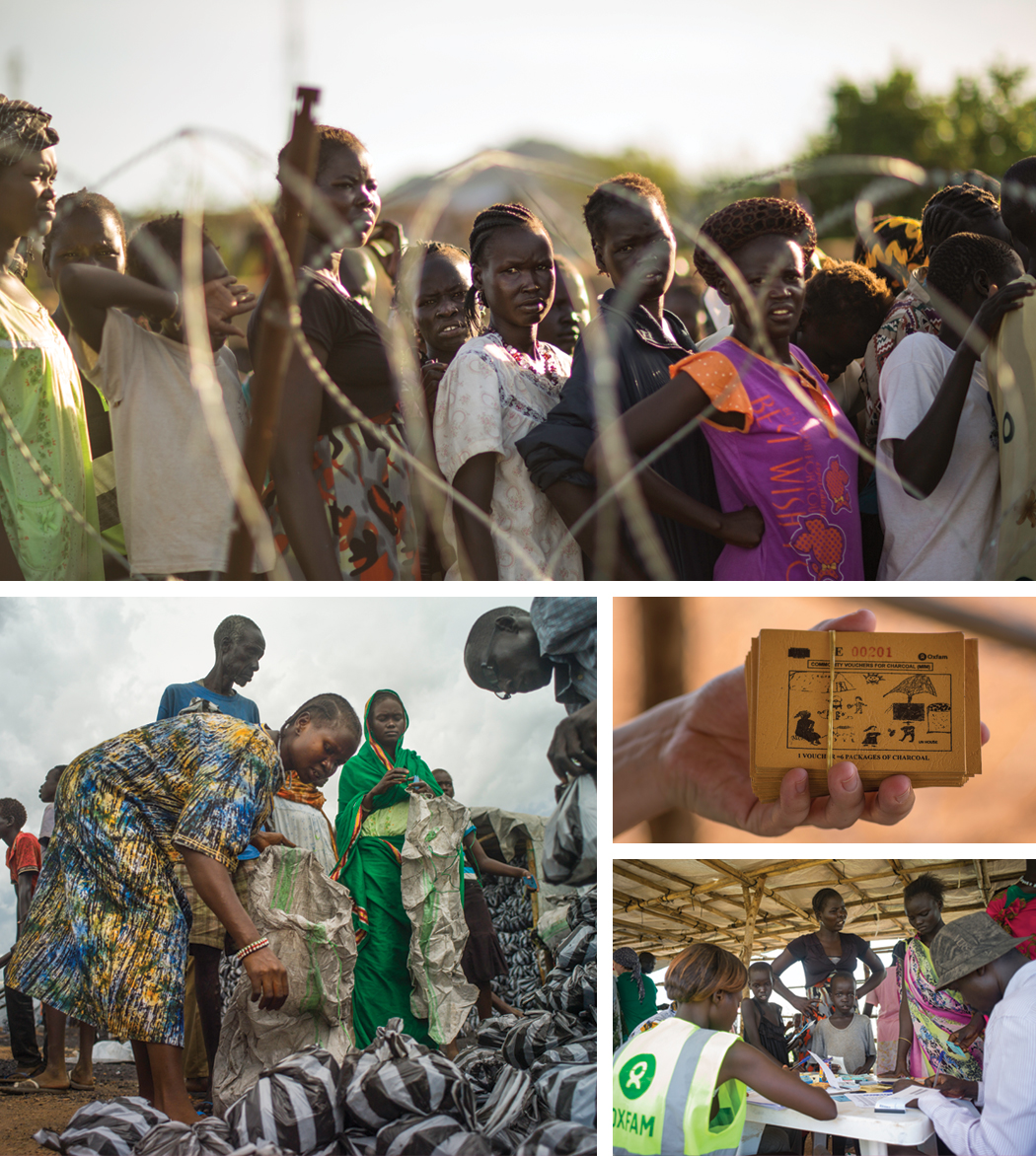

Above: Oxfam has been distributing charcoal in the camps in Juba. It is unsafe for the residents of the camp to leave to collect firewood so have been struggling to cook food due to lack of fuel. Photos: Kieran Doherty / Oxfam

During a typical day, I get up around 7ish and I arrive to the office at 8.10am. I spend the first few hours catching up on office work, such as signing off on financial requests and budgets, looking at team plans, recruitment, logistics, funding, and working on our programme strategy etc.

Then I usually head to the camps at around 12.30pm, which are around a 30 minute drive away. I manage Oxfam’s humanitarian response in a place called UN House in Juba, which is a UN base and has three big camps in it with 25,000 people who have fled the conflict. As I am the external representative for Oxfam’s response in UN House, I attend coordination meetings with other aid agencies, the UN police and peace-keepers in order to represent Oxfam’s work. There are several of these per week.

Then I pop in to the camps, check on the activities the team are doing and troubleshoot issues on the spot. This can be anything from supply issues, to queries from the community leaders about our work and selection of beneficiaries. The other day I was out with some of our new charcoal vendors and we went around the camp to map out the site selection of where they were to build their charcoal shops, marking out the site in the mud and with stones- not a very sophisticated way of site-mapping but it did the job!

Every month food distributions take place in the camps over 10 days. At a food distribution, Oxfam provides people with vouchers for charcoal (used as a fuel to cook food) that they can redeem with various vendors who have set up in the camp. We also give people vouchers to use milling machines, so they can mill the grains given to them by the World Food Programme to make flour, etc. Another reason why access to a milling machine is so important is because grain that is unmilled can make small children very sick. If there is a distribution going on that day, we head in early to get set up- usually we arrive at 9am. I help make sure the distribution goes smoothly, everyone receives assistance and the team are kept safe. When you’re out in the camps under the hot sun it can be exhausting. Distributions are particularly hectic due to the volume of people so lunch is always missed!

At around 5pm it could be back to the office where I would be working with the finance and logistics teams making sure we have our supplies in and everyone is being paid, working with the funding team to make sure we are up to date with our donor reporting, and the policy team on any messages that we need to advocate certain stakeholders on. These days a lot of time is spent on recruitment as we’re scaling up our team because the needs are growing even greater and we are now entering in a new phase of our response where we are doing more activities in the camps.

![]()

Clockwise from top: The majority of Oxfam staff are locals: Lam Jacob, Susan Angwech, JAcob Achiek, Mayok Ayuen Garang Photos: Kieran Doherty / Oxfam

Since December, we have reached 261,000 people at several locations across South Sudan with food, clean water, sanitation, hygiene materials and other essentials from fuel to solar lamps.

Around four million people need urgent humanitarian support now – including 200,000 children suffering severe acute malnutrition. The conflict meant that people couldn’t plant crops earlier this summer and the country is on the brink of a massive food crisis, with a total of 7 million people facing hunger in the months ahead.

I try to finish up in the office at around 7pm. I then grab a bite to eat back at the house and then it’s back onto the laptop for more emails in the evening. One of the main dominating factors for expats here is the 9pm curfew which is pretty standard among the NGOs. If we do get time to go out after work, we usually have to down our drink and get our food to go as we are always rushing to leave to make sure we are home in time for 9pm!

All of us working here have security training, access to equipment such as satellite phones, and follow a number of security procedures. When we’re working in the camps we have to be clearly identifiable as working for Oxfam and have our car on standby during distributions in case we have to evacuate from the camps if an incident broke out.

The majority of Oxfam staff are locals. We also have one or two staff members who are among those living in the camps, highly educated people who have like over a million others been forced to flee their homes because of the conflict that broke out in December 2013. It’s great to be able to give people who have been through so much the opportunity to be part of the team and the emergency response work.

There are a lot of people who had good lives before the conflict happened. They had a home with their family, they earned a living, some are highly educated and skilled. Life as they knew it was destroyed when this crisis began. When the fighting broke out they either had to just leave everything behind or else their goods and homes got looted or destroyed so they have nothing to return to.

I imagine my family home in suburban Dublin and then suddenly military start rolling in, bombs start dropping down on you, and your house and everything you had was destroyed, and you find yourself living in a camp overnight sometimes in cramped conditions and perhaps sharing your tent with total strangers, many not knowing where their family members are. It’s a highly distressing situation for these families.

A lot of people in the camps are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. I find sometimes that the kids are a lot more reserved and easily frightened than children from outside of the camps, which is definitely a sign of everything they’ve been through. People are frightened and not considering going home yet because they don’t feel it’s safe. There are a number of threats such as violence, unlawful detention, theft that happens for people who even just leave the camp to go the local market in Juba which can be dangerous if you are from a particular tribe.

![]()

Clockwise from top: Elizabeth and baby Swampy. Elizabeth was heavily pregnant when she fled the conflict in South Sudan, forced to hide and then give birth in a swamp. A water tanker filling up an Oxfam bladder tank. This will supply families living in Mingkaman with clean water. Children wash their hands at an Oxfam health training session Photos: Kieran Doherty / Oxfam

The work here is very intense and all-consuming, but at the end of the day that’s also why I’m here. As cheesy as it sounds, I do really believe in what we’re doing here and I believe in the team doing it. I work with some amazing people who are also equally passionate about what we do. It can be quite an inspiring environment to work in.

We get one week off for every 10 weeks in country to help compensate for the intense hours. My plan for next R&R (rest and relaxation) later this month is to go to Ireland and England so I’m very excited about that and I’m going to tag on some annual leave days so I have a two week break in total. There are so many things I’m excited about for my holiday home- of course seeing family and friends are at the top of my list, but also home cooking, brown soda bread, cinema, cocktails and definitely hot showers!

I wouldn’t encourage friends or family to come and visit me here in South Sudan. At the end of the day it’s a conflict zone and I wouldn’t want to put them in a situation they’re not prepared to deal with.

There are a couple of Irish people here in Juba working for other NGOs, there’s one or two I’ve met and then you hear rumors ‘there’s more Irish people around!’, so I need to try and track them down, in a non-stalker way!

It was nice to have colleagues from Dublin over recently – when you meet another Irish person you automatically have a lot of in-jokes which other nationalities don’t necessarily understand, in terms of slang, the banter, and also references to Father Ted jokes that get lost on other people!

So where to next? I will be here in South Sudan for another several months working on the emergency response with Oxfam and after that it all depends on what opportunities comes up and also where my boyfriend gets posted to next. We will look at somewhere overseas where we can both work like a developing country or else we might go back to London for a few years and then go overseas after that for a while.

At the moment if I could pick anywhere, I would love to work in Palestine – a place I’ve always been interested in and I’m watching what’s going on in Gaza there at the moment- it is something we talk about a lot here in the Oxfam house in South Sudan. Otherwise I love East Africa so ideally I’d like to stay working somewhere near here but at the same time if I do end up in London next for the next few years I’d be very happy with that. It would be nice to be back, closer to home, and have a sense of normality for a while, because it is very intense working out in the field, especially when you are doing postings like Pakistan and South Sudan back-to-back. It might be nice to have more of a normal life and working hours before venturing back out overseas again.

If you'd lke to support our work in South Sudan, please donate online to Oxfam Ireland’s emergency response or visit your local Oxfam shop.